“Warning shot” Daleks

Yes, the first foray to Skaro for the Doctor was where he met a kinder, gentler Dalek race. The cliffhanger scene of Episode 1 is the world’s first glimpse of a Dalek: we see only an arm-stalk and sucker point-of-view shot, closing in on a terrified Barbara, spreadeagled on a metal wall. For those of us from Who‘s future, it’s a thrilling piece of history. And, it’s precious imagining what must have run through the minds of those children who’d never seen a Dalek before–what could be threatening Barbara?!

Yes, the first foray to Skaro for the Doctor was where he met a kinder, gentler Dalek race. The cliffhanger scene of Episode 1 is the world’s first glimpse of a Dalek: we see only an arm-stalk and sucker point-of-view shot, closing in on a terrified Barbara, spreadeagled on a metal wall. For those of us from Who‘s future, it’s a thrilling piece of history. And, it’s precious imagining what must have run through the minds of those children who’d never seen a Dalek before–what could be threatening Barbara?!

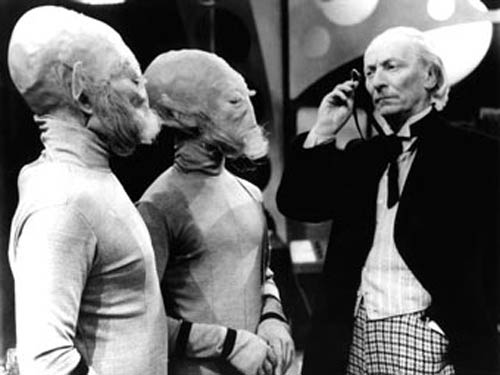

Our second glimpse is in Episode 2. We hear the first Dalek words ever, the unimpressive: “You will move ahead of us and follow my directions. This way.” The Dalek’s eye stalk swivels a full 180 degrees to face the TARDIS crew: “Immediately!” it commands. Man, these toilet plunger dudes are bossy. It’s this scene, the command and eye-swivel, that evoked the first frisson of excitement in me, reminding me of “my” Daleks. Authoritarian, abrupt, Dalek-like is this–to me, this scene is really where the Daleks are born.

Strangely, the rules of engagement of The Daleks Daleks are even more restrictive than those of five hundred years earlier in Genesis of the Daleks. In this second-ever scene featuring Daleks, Ian doesn’t take kindly to being bossed around, and he runs. This is somewhat counter-intuitive given Ian’s character: he and Barbara are the level-headed ones. And in my experience, when being bossed around by an entirely new race, without more information, running just doesn’t seem called for. But apparently Ian’s had it with being kidnapped by the difficult Doctor, and the bossy tin pots have pushed Ian over the edge–and he runs.

Happily for Ian, these Daleks are nice: refusal to cooperate apparently requires only a temporary paralysis ray to the offender’s legs. Unlike the Daleks we know from Genesis and every other story, these Rules of Engagement require warning/nonlethal shots first. Lucky Ian.

And if Ian repeatedly disobeys the Daleks? Even luckier Ian! The Daleks warn that a second instance of disobedience will result in… Nope, you guessed wrong, not extermination–instead, permanent paralysis of the legs! Man, these Daleks are nice! But as you’ll see, kindness doesn’t survive their first serial, though after reflecting on the seven episodes I can’t quite figure out why the Daleks’ rules of engagement and strategic outlook suddenly changed. Needless to say, it works out in the end: regardless whether it makes any sense, the reflexively nasty Daleks that emerge by the end are much, much better villains.

And if Ian repeatedly disobeys the Daleks? Even luckier Ian! The Daleks warn that a second instance of disobedience will result in… Nope, you guessed wrong, not extermination–instead, permanent paralysis of the legs! Man, these Daleks are nice! But as you’ll see, kindness doesn’t survive their first serial, though after reflecting on the seven episodes I can’t quite figure out why the Daleks’ rules of engagement and strategic outlook suddenly changed. Needless to say, it works out in the end: regardless whether it makes any sense, the reflexively nasty Daleks that emerge by the end are much, much better villains.

It’s not until Episode 4, the third time the Daleks engage, that the Daleks finally progress to their storied “examination.” It’s in the run-up to the ambush of the Thals that we discover the Daleks’ intent in inviting the Thals to partake of a sample of the promised “unlimited supplies” of “fresh vegetables” and food bounty carefully laid-out in the entrance building to the Dalek city: “make no attempt to capture them–they are to be exterminated.” But this still isn’t “our” Daleks: this slaughter is entirely premeditated, well thought-out beforehand, carefully planned. So really, nowhere in The Daleks are the Daleks the knee-jerk bloodthirsty, exterminate-for-any-obstreperousness foes that we love to hate.

What exactly indicated a need to convert the Daleks we first encounter into all-death all-the-time is probably the writer’s realization that any metal-enclosed faceless race that plots the wholesale destruction of another species by pouring radiation into the atmosphere probably shouldn’t have any redeeming qualities. The writers probably realized that temporary paralysis of foes is an unrealistic (and not a tension-building) M.O. for what turned out to be, ultimately, a conscience-less species.

Slowly the Dalek history emerges. We’re on Skaro, the 12th planet in the solar system. 500 years ago a neutron war rendered the planet nearly inhabitable. Two races fought in the war, each believing the other totally annihilated: the Thals and the Dals (five centuries before, in Genesis of the Daleks, these Dals called themselves the “Kaleds”). The atmosphere now registers radiation at dangerous levels.

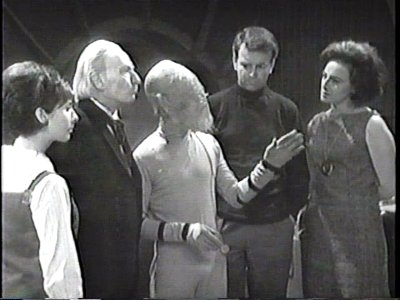

The Thals apparently are the least curious race in the universe, never having thought to descend down to the Dalek’s city for five centuries to discover if their adversaries were totally destroyed by the neutron war. (But they are curious enough to stalk strangers in the forest and leave nondescript and unlabeled vials of anti-radiation medicine in the off chance the strangers can figure out what the vials are for!) Susan isn’t bothered by this, gushing on about how the Thals are “perfect” and “magnificent people.”

The Thals apparently are the least curious race in the universe, never having thought to descend down to the Dalek’s city for five centuries to discover if their adversaries were totally destroyed by the neutron war. (But they are curious enough to stalk strangers in the forest and leave nondescript and unlabeled vials of anti-radiation medicine in the off chance the strangers can figure out what the vials are for!) Susan isn’t bothered by this, gushing on about how the Thals are “perfect” and “magnificent people.”

The Thals believe themselves to be the only survivors of the neutron war, and they port around their entire history inside a small metal box. Their history appears to be stored on 16mm film reels and on artistic representations of the Thals and Daleks painted on hexagonal black slates. We’re treated to the art of what the Thals looked like pre-neutron war: basically blonde pseudo-Norse warriors. The Doctor sees, but the viewer does not, the hex art depicting what the Daleks used to look like.

Not only do the Daleks lose any chance at a conscience by the end of The Daleks, but several other tropes are set so firmly after this serial’s critical success with its 60s’ audience that The Daleks never escape them to this day: (a) the odd, misshapen archways of Dalek corridors; (b) the lovely dual-pulse throb of the Dalek control room introduced in Episode 2 is almost exactly the same as the one we hear in RTD episodes; (c) the Dalek’s penchant for circular dials and circular view screens; (d) the spastic sucker-stick movements. Yes, today’s Daleks are the epitome of throwback sci-fi.

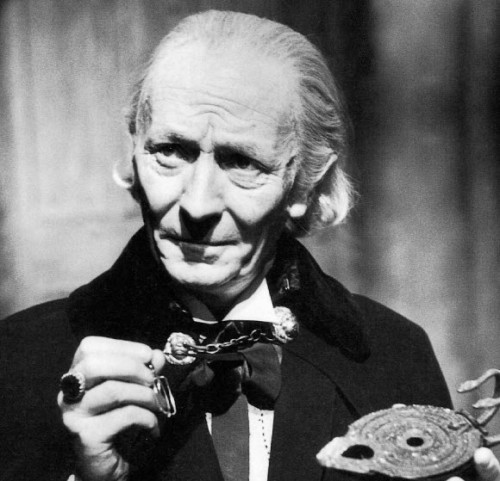

Dangerous Doctor/Ian Ascendant

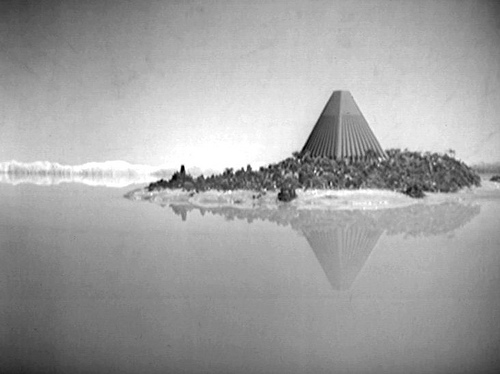

Right from the beginning, as in Unearthly Child (my review of Ep 1 here) the Doctor continues to confront Ian and Barbara. Ian blames the Doctor for “uprooting” them, and the Doctor counters, justifying his kidnapping of the two teachers, that they “barged in” to his TARDIS. And after seeing the magnificent and gleaming buildings of the city in the valley, the Doctor sabotages the TARDIS by removing the mercury from the “fluid link,” schemingly devising a plan to visit the city to find replacement mercury. Luckily, he quickly admits in the beginning of Episode 2 that he sabotaged the TARDIS so that he could investigate the fascinating gleaming city.

What’s beautiful and a great piece of acting is Ian’s reaction to this admission: “you fool you old fool,” Ian storms, “it’s time you faced up to your responsibilities. You got us here, now I’m going to make sure you get us back.” This is prelude to Edge of Destruction, where the Doctor, as I’ve discussed, turns the corner and makes Who what it is today. And it’s also a demonstration yet again that Ian and Barbara are us–the Companion as viewer.

This is becoming Ian’s hallmark: confronting the Doctor’s constantly putting the crew and others in danger without consideration of the risks. In Episode 5, Barbara realizes the crew will never be able to leave Skaro until they can recover the fluid link, which Ian accidentally left behind in the escape from the Dalek city. The Doctor hatches a plan to have the Thals attack the Daleks as a diversion so the crew can slip in and recover the fluid link. But again it’s Ian that opposes the Doctor, rejecting that a fluid link is sufficient spoils for a Thal war party that has no weapons. He explicitly tells the Doctor that he’s challenging the Doctor’s leadership of the TARDIS crew.

This is becoming Ian’s hallmark: confronting the Doctor’s constantly putting the crew and others in danger without consideration of the risks. In Episode 5, Barbara realizes the crew will never be able to leave Skaro until they can recover the fluid link, which Ian accidentally left behind in the escape from the Dalek city. The Doctor hatches a plan to have the Thals attack the Daleks as a diversion so the crew can slip in and recover the fluid link. But again it’s Ian that opposes the Doctor, rejecting that a fluid link is sufficient spoils for a Thal war party that has no weapons. He explicitly tells the Doctor that he’s challenging the Doctor’s leadership of the TARDIS crew.

It’s a nuanced series of scenes, and Ian eventually adopts the Doctor’s plan, admitting to Barbara that without the fluid link, the crew will die on Skaro. Ian takes a further step and adopts the Doctor’s manipulative tactics, searching desperately for what will make the Thals fight. First, he callously threatens to destroy the entire remaining history of the Thal race–the film reels and hexagonal art pieces. But the Thals don’t bite. Second, Ian threatens to kidnap and deliver to the Daleks the pretty blonde Thal Dyoni, the prominent Thal Alydon’s love interest.

This works, and Alydon launches himself at Ian, slugging him. Alydon then gives a Henry V at Agincourt-worthy speech, calling the Thals to fight with the crew: either we die here for lack of food, or we wait for the Daleks to kill us, or we go now to the city, where there is ample food. Alydon points out that the Thals’ and crew’s interests are the same. It’s a good speech, well delivered–in fact, of the six episodes of overacted and hammy Thal characterizations, this speech is a standout. One great line: “There is no indignity in being afraid to die. There is a terrible shame in being afraid to live.”

This works, and Alydon launches himself at Ian, slugging him. Alydon then gives a Henry V at Agincourt-worthy speech, calling the Thals to fight with the crew: either we die here for lack of food, or we wait for the Daleks to kill us, or we go now to the city, where there is ample food. Alydon points out that the Thals’ and crew’s interests are the same. It’s a good speech, well delivered–in fact, of the six episodes of overacted and hammy Thal characterizations, this speech is a standout. One great line: “There is no indignity in being afraid to die. There is a terrible shame in being afraid to live.”

But Ian’s turnaround rings untrue: it’s unusual and out of character that Ian’s solid moral compass would swing from principled to manipulative, a la the Doctor’s reviled tactics, so quickly. Moreover, proving pacifism wrong by threatening Alydon’s love interest smacks of simplistic plot development by the Who writers. And finally, that threatening Alydon’s love interest would not only turn around his pacifism, but make an inspiring military leader able to belt out an inspiring “join me to the death” speech, is just unbelievable. Still–the speech is great, no matter how Ian got Alydon there.

The continuity concept

On display again is the show’s early years’ serial-to-serial “continuity” concept, where each story flows seamlessly into the next. Not only does the TARDIS lurch at the end of The Daleks into the very crash that begins the next serial, Edge of Destruction, but one of the primary themes of Edge is seeded in The Daleks. Right at the beginning of Episode 1, Barbara asks Susan if there isn’t some device in the TARDIS that records their journeys. Yes, Susan says: “there’s a meter affixed to a great big bank of computers. If you feed it with the right sort of information it can take over the controls of the ship and deliver you to anyplace you want to go.” Hence as much as Barbara wants the Doctor to take them back, Susan says, the Doctor’s forgetfulness prevents him from being able to enter the “right sort” of information! Too bad Susan is always screaming, because one would think, as brilliant as she is–she reads books in Unearthly Child at inhuman speeds–that she’d be able to enter the “right sort” of data. (As I sit in the car on vacation with my kids writing this and listening to The Sensorites, I know that Susan will be taking a lead, non-screamer role in future episodes, so her early brilliance in Unearthly Child seems set to return.)

Bottom line: Ponderous, and Muddled

Overall, The Daleks is a piece of Who history that shouldn’t be missed. But it suffers a few critical flaws.

First, it’s slow moving. Whole episodes are Web Planet-painful in their long, slow, sequences in which little is said and little happens. Episode 1 is solid. Episodes 2, 3, and 4–over an hour–are just painful, and witness endless scenes of Ian rubbing his legs, the captive crew languishing in the Dalek city, and Susan’s annoying fawning over the “perfect” Aryan Thals (compare and contrast with the “master race” spouting Daleks… Is this meant to point to a flaw in Susan, or is it simply a bias in the writers? Most latter day “classic,” RTD, and Moffat Who sport a Doctor in a virtual love affair with alien life of all levels of “prettiness.”)

Episode 5 is a return to form, with the inspiring (but plotwise problematic) Alydon speech calling the Thals to war. Episode 6 is back to painful pacing with long slow scenes in the caves leading to the Dalek city and painful acting by the doughy and cowardly Thal Antodus who persistently whines, eating up way too much screen time, that he wants to return home, and eventually, and literally, drags down the expedition. Episode 7 is another mixed bag, graced by the thrilling and well paced (but idiotic and humongous plot hole) mass-test of the unknown Thal drug and later scheming to irradiate all of Skaro’s atmosphere.

Episode 5 is a return to form, with the inspiring (but plotwise problematic) Alydon speech calling the Thals to war. Episode 6 is back to painful pacing with long slow scenes in the caves leading to the Dalek city and painful acting by the doughy and cowardly Thal Antodus who persistently whines, eating up way too much screen time, that he wants to return home, and eventually, and literally, drags down the expedition. Episode 7 is another mixed bag, graced by the thrilling and well paced (but idiotic and humongous plot hole) mass-test of the unknown Thal drug and later scheming to irradiate all of Skaro’s atmosphere.

Second, it makes no sense that 500 years would pass, but neither the Thals nor the Daleks have any idea that each other exist. After all, the Thals have been encamped, of all the possible places on Skaro, on the plateau directly overlooking the Dalek city.

Third, the Daleks progress from bossy and utilitarian tin pots–they explicitly reason that they will preserve the TARDIS crew because they may have some use in the future–to bloodthirsty and irrational: “the only interest we have in the Thals is their total extermination” and “tomorrow we will be the master race of Skaro!”. But this progression is on a dime, and it doesn’t survive the common sense test, if applicable to tin pots from Skaro.

They turn this corner only after inexplicably mass administering the Thal’s anti-radiation drug to Sections 2 and 3 of the Dalek City. Why the Daleks would, after 500 contented years within their sealed city, run a mass trial of an unknown drug, is mystifying. Or at least, there’s no given motive. We know the atmosphere still registers radiation at dangerous levels, and started to kill the TARDIS crew. Also: why the Daleks would want to leave their city, since to move they need the static electricity delivered through their city’s generator and metal floors, equally is a motive that escapes me. I suppose they could be fickle in their philosophy, as Alydon of the Thals turns out to be, but I don’t get it. I’d think since they appeared at first to be utilitarian and somewhat logical, the solution to stopping Dalek deaths from anti-radiation drug overdoses would be to kick the habit of mass-administering unknown drugs. But that’s just me.

Some closing trivia

The first Daleks story is rife with interesting trivia. Here’s a few: (1) Ridley Scott, famed director of Blade Runner and Gladiator among others, was assigned to design the Daleks–their shape, look, and feel–but a twist of fate interfered with Scott’s schedule, leaving Raymond Cusick to take the job. How the Daleks might have looked different had that not happened! (2) The Daleks almost wasn’t produced, since, according to the first script editor David Whitaker, the Daleks themselves were seen by some in the BBC as “too childlike” and inpinging on the goal to make Who an educational show. (3) the Who writers intended the Daleks to be retired after The Daleks–only because they took England by storm did they return. As it is, the Daleks have appeared in 102 Who episodes since 1963–more than any other enemy, according to this super-handy data sheet released by xxnapoleonsolo in June 2011 (4). As Episode 3 ends we see the first ever glimpse, and the only one on screen in this serial, of what’s inside the shell: in the closing shot we see a clawed hand creep out of under the cloak the Doctor and Ian wrapped the mutant in. Funny trivia: evocative as it is, it’s just a joke shop gorilla hand smeared in grease!

The first Daleks story is rife with interesting trivia. Here’s a few: (1) Ridley Scott, famed director of Blade Runner and Gladiator among others, was assigned to design the Daleks–their shape, look, and feel–but a twist of fate interfered with Scott’s schedule, leaving Raymond Cusick to take the job. How the Daleks might have looked different had that not happened! (2) The Daleks almost wasn’t produced, since, according to the first script editor David Whitaker, the Daleks themselves were seen by some in the BBC as “too childlike” and inpinging on the goal to make Who an educational show. (3) the Who writers intended the Daleks to be retired after The Daleks–only because they took England by storm did they return. As it is, the Daleks have appeared in 102 Who episodes since 1963–more than any other enemy, according to this super-handy data sheet released by xxnapoleonsolo in June 2011 (4). As Episode 3 ends we see the first ever glimpse, and the only one on screen in this serial, of what’s inside the shell: in the closing shot we see a clawed hand creep out of under the cloak the Doctor and Ian wrapped the mutant in. Funny trivia: evocative as it is, it’s just a joke shop gorilla hand smeared in grease!

Lime’s advice: The Daleks is historic, but plotwise it barely holds water. Four episodes are painfully slow, and the Ziggy Stardust Thals are burdened by some of the worst acting this side of daytime soaps. Convict!

Lime’s advice: The Daleks is historic, but plotwise it barely holds water. Four episodes are painfully slow, and the Ziggy Stardust Thals are burdened by some of the worst acting this side of daytime soaps. Convict!

When I was wee, I threw myself headlong into Doctor Who. I collected the books, watched the shows when my local stations could afford them (largely accomplished via zealous and frequent fan-run fund drives). But I ached for something more serious than the average fan ‘zine, something that could explain to my young mind why Doctor Who had lasted so long, why it was unlike any other show I’d seen, pourquoi la difference.When I started Who, it was already about fifteen years old. Next year, in 2013, Who turns fifty. Yes, the big 5-0. The

When I was wee, I threw myself headlong into Doctor Who. I collected the books, watched the shows when my local stations could afford them (largely accomplished via zealous and frequent fan-run fund drives). But I ached for something more serious than the average fan ‘zine, something that could explain to my young mind why Doctor Who had lasted so long, why it was unlike any other show I’d seen, pourquoi la difference.When I started Who, it was already about fifteen years old. Next year, in 2013, Who turns fifty. Yes, the big 5-0. The